The Not-so-Smart Thinking Machines and the International Bureaucrats

Special Agreement Submitting a Dispute to the International Court of Justice

The Republic of Brythos (“Brythos”) and the Federation of Quirmania (“Quirmania”) (together, “the Parties”);

Considering that differences that have arisen between them concerning the status of Terranova, an autonomous region of Brythos, and alleged interference by Brythos in Quirmania’s internal affairs through the development and deployment of artificial intelligence systems to generate and disseminate disinformation intended to promote separatism in Terranova;

Recognizing that the Parties are both Contracting Parties to the Uberwaldian Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law (the “Responsible AI Convention”);

Noting that diplomatic efforts and negotiations undertaken since the events described below have failed to resolve the dispute;

Desiring to submit the dispute to the International Court of Justice (“the Court”) for final and binding adjudication;

Have concluded the following Special Agreement (“Compromis”):

1. The Parties submit the questions contained herein to the Court pursuant to Article 40(1) of the Statute of the Court. The applicable law shall be that set out in Article 38(1) of the Court’s Statute.

2. It is agreed that Quirmania shall appear as Applicant and Brythos as Respondent. This designation is without prejudice to any question of the burden of proof.

3. The Court is requested to determine the legal consequences arising from its judgment, including the rights and obligations of the Parties.

4. The Parties undertake to accept the judgment of the Court as final and binding and to execute it in good faith.

Done at The Hague on this day, in the English language, in two originals.

Signed For the Republic of Brythos For the Federation of Quirmania

Factual Background

I. Story of Uberwaldia, Quirmania, Brythos andTerranova

II. Rise of AI and the Responsible AI Convention

III. Terranova Quest for Independence

IV. Questions for the Court

I. Story of Uberwaldia, Quirmania, Brythos and Terranova

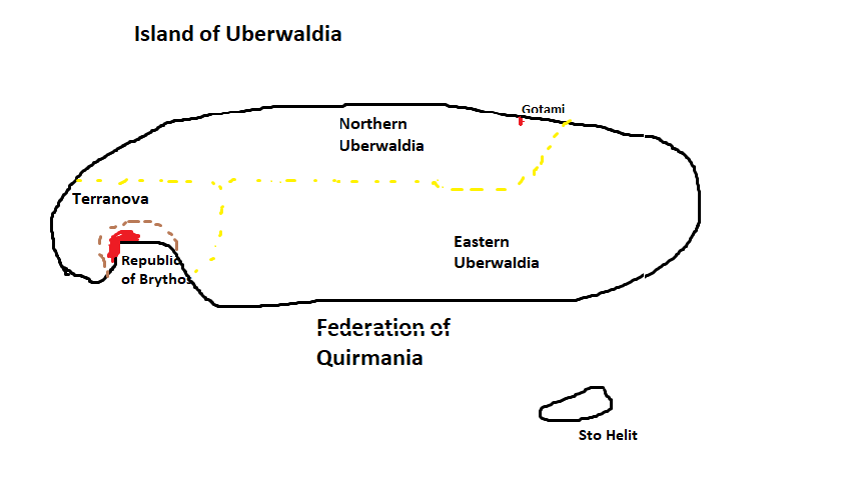

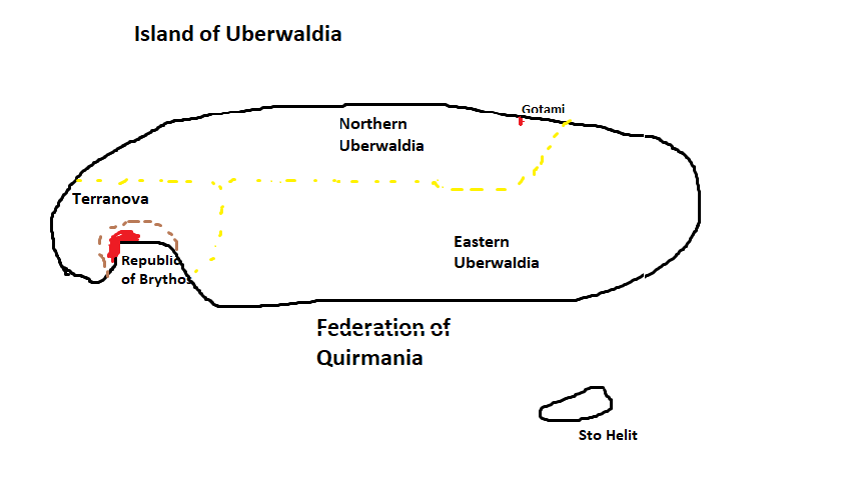

1. Uberwaldia is a sprawling and mountainous island in Southeast Asia, near the straits of Malacca. Located near the divide between the Indian and Pacific Ocean, Uberwaldia historically sits in the middle of many maritime trade routes.

2. The island is currently divided between two States: The Republic of Brythos (“Brythos”) and the Federation of Quirmania (“Quirmania”). These states are very distinct between each other but share a common colonial past.

3. In the southwestern part of island, there is a particular large enclave with a natural bay and shallow waters. This region of the island was settled by the brythosi people, which founded the city of Ankh-Morport in the 350 BCE., initially a fishing town which grew over the centuries as a trade port. The brythosi people were primarily fishermen and merchants, taking advantage of their geographic location to engage in trade with other islands.

By 1100 CE., Ankh-Morport was considered by many a mandatory stop in the southeast Asian trade routes, rivalling Malacca, Palembang, and the later-founded cities of Jambi, Batavia, Singapore and Manila. The city was crucial for those procuring spices, such as cloves and nutmeg, and luxury goods from China, such as porcelain and silk.

Initially governed by a monarchy, the city underwent dramatic change in 1246 CE following a particularly brutal succession war. During the conflict, massive fires ravaged the port and decimated most of the merchant fleets. In the aftermath, the monarchy was overthrown, and the wealthiest families seized control, establishing a merchant republic. Because of its origins amid the flames and the institution of a network of fire stations with mandatory service requirements, this new regime—where only these elite families could be elected to power by a narrow segment of the populace—became known in history as the "Firefighters' Republic". The Head of the Government, the Domnule Pompier, would traditionally wear a similar helmet than those employed by the firefighters across the city.

The merchant republic of Ankh-Morport and the Brythosi people has been historically considered tolerant, with many cultures and religions coexisting in the city-state. Nevertheless, since the IXth century, the majority of the population has subscribed to ZenZeninism.

4. The Quirmani people migrated to the island of Uberwaldia in the VIIth century CE. It is estimated that they arrived in several phases, fleeing from persecution in Borneo, and established themselves across the northern and eastern part of the island, initially as semi-nomad people, mostly as shepherds.

5. This changed in the Xth century CE., where the vast majority of the Quirmani people converted to the religion of the Waxing Crescent Moon and began establishing permanent settlements across Uberwaldia. These began with the construction of beautiful magnanimous temples, from which towns and sprawling cities grew around. During this period, between the X-XV centuries, several quirmani kingdoms were established. While many tried, none of these accomplished the “Quirmani Dream” of Mahaprajapati Dai (quirmani poet, 1223-1254 CE.) of unifying the quirmani people in Uberwaldia under one kingdom.

6. The coexistence of these quirmani kingdoms with the brythosi city-state was characterized by frequent conflicts, with many of the former regularly attempting to conquer the later. None of these were successful, with the city-state employing many tactics to drive-off the invaders, such as the construction of strong fortified walls cutting the city from the land in the XIth, to “bribing” other quirmani kingdoms to fight on their behalf. The writings of Mahaprajapati Dai include passages that describe this frustration “Our people will never be whole unless the brythosi are expelled to the sea, and we will never be able to defeat them until we fight as one. That is the eternal struggle that trumps our dream. They will always find a way to turn us against each other, to turn brother against brother.”

Nevertheless, the city of Ankh-Morport never grew inland beyond the XI century wall, due to the frequent razzings by miscellaneous quirmani forces.

7. The story of Uberwaldia changed dramatically during the XVI century with the arrival of the European nations to the Indian ocean. The Portuguese and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) coveted the control of Ankh-Morport and its trade routes. The city-state was able to avert its conquest for some decades but ultimately fell in 1552, under the dominion of the Empire of Smallopia. The helmet of the last Domnule Pompier was melted into a key, given to the new viceroy appointed by Smallopia. This European empire had small possessions and fortified trade ports in modern day Nigeria, Somalia, Yemen, Bangladesh and Ank-Morport. Their strategy of attempting to control the flow of commerce from Southeast Asia to Europe had middling success. Crucially, it neglected any attempt to project power within Uberwaldia itself.

8. The second phase of the colonization of Uberwaldia occurred in 1691-1720, where the Empire of Llamedos conquered all the quirmani kingdoms, unifying the island (with the exception of Ank-Morport) under their control. In 1802, Llamedos formally dissolved all administrative and political divisions of its dominion on Uberwaldia, restructuring its possession into 3 administrative regions: Northern Uberwaldia, Eastern Uberwaldia, South-Middle Uberwaldia. South-Middle Uberwaldia (later known as Terranova) was the smallest of these regions, comprising the territory surrounding Ank-Morport.

9. In the War of Tulips of 1854-1855, the Empire of Smallopia was annexed by the just-reunified Pastalini Empire. Smallopia’s colonies through the coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean were divided by many colonial powers. In the case of city-state in the Uberwaldia, Llamedo forces immediately moved in, capturing the city and definitely unifying the island under their colonial rule. Ank-Morport and its territory became the 4th (and smallest) administrative region.

10. Llamedo governed Uberwaldia with brutal force for a long period, until the Second World War. However, not all the indigenous people were treated the same. Ank-Morport prospered in this period, becoming the capital of the Llamedian Uberwaldian Dominion, on which all colonial administrative institutions were based in.

The brythosi were frequently preferred for administrative positions in these institutions, and to the many trading companies and bodies.

Without the historical threats of quirmani raiding parties, and the rise in commercial activity, Ank-Morport grew exponentially in all directions, beyond the medieval walls which had contained it, and into the sea.

The brythosi population also exploded in numbers. For the first time in its history, the brythosi started moving in great numbers into other parts of Uberwaldia. The majority of these settled in South-Middle Uberwaldia, leading to the rapid urbanization of this region. By 1926, the region was renamed Terranova. Census from this period indicate that Brythosi were approximately 40% of the population of the region, and nearly 80% if only the cities were accounted for.

In contrast, the regions of Northern Uberwaldia and East Uberwaldia were exclusively viewed by the Llamedian authorities for resource extraction purposes.

11. The Second World War dictated the decline of the Llamedian Empire. During the conflict, Llamedian access to Uberwaldia was cut-off by the Nippongying Empire, with Ank-Morport and Terranova being fully occupied. Northen and East Uberwaldia regions successfully resisted the advancements of enemy forces, exploiting the mountainous terrain.

12. After the war ended, Llamedian authorities were not warmly received back in Uberwaldia. Bythosi people resented the abandonment under the nippongying occupation and the quirmani rejected the return of the colonial authorities after enjoying autonomy for almost 5 years after centuries of exploitation.

13. The Empire of Llamedos began the process of withdrawal from Uberwaldia in January 1946, creating a Commission for the transition period. The Transition Commission began its by works by establishing negotiations with the organizations that arose during the occupation/resistance period, local and regional and religious leaders. In parallel, it began a massive census of the entire population of the island, to prepare elections initially scheduled to July 1947.

The initial proposal by the Empire of Llamedos and prepared by the Transition Commission was for the Uberwaldian Domminion to become a sole independent state, a federation composed by the regions of the island. The project for a Federation of Uberwaldia would be multiethnic and multireligious republic with the capital in Ank-Morport. Initial results for census indicated that this federation would have a population with the following composition: 39% Brythosi, 57% Quirmani, 4% other ethnicities, 41% ZenZeninism, 55% Waxing Crescent Moon, 4% other religions. This proposal was welcomed by the Brythosi representatives but rejected by the Quirmani delegations.

The Transition Commission proposed further amendments for this proposal, including granting further autonomy to the regions, the capital of the federation in Gotami (the biggest quirmani city). Nevertheless, no matter the concessions, the quirmani delegations were nearly unanimous in advocating for the expulsion of Ank-Morport from the federation.

The Transition Commission dropped its single-state solution in early 1947, advancing then to a two-state solution: a brythosi republic and a quirmani federation. Due to considerations regarding the minorities of brythosi in the quirmani regions, especially Terranova, the Transition Commission prepared a package of proposals to ensure the peaceful transition of power. This included a set of compromises for the would-be Quirmania regarding its brythosi minorities, and new borders between the states, where localities with a majority of brythosi would be transferred to the brythosi republic, to be determined using the data from the census.

14. On 31st December 1947, the quirmani authorities (elected in July 1947), proclaimed unilaterally the independence of the Federation of Quirmania, comprised by the Northern, Eastern Uberwaldia and Terranova regions, without any changes to the 1802 colonial borders. The new federation proclaimed the Waxing Crescent Moon as its official religion, while also subscribing to the principle of freedom of religion, and assumed a set of compromises to protect the cultural, political and religious autonomy of its bythosi citizens in the Terranova Region. According to the 1946 census, the Terranova region was comprised of 45% brythosi, 48% quirmani, 7% other ethnicities.

15. On 5th January 1948, the Republic of Brythos declared its independence, comprising the city of Ank-Morpork and the surrounding municipalities, without overstepping the borders proclaimed by the Federation of Quirmania. Brythos attempted from the beginning to negotiate the transition of several municipalities near its border with large majorities (>80%) of brythosi people. Quirmania denied of these requests.

Following the declarations of independence, large numbers of brythosi migrated across Uberwaldia, from the Northern and Eastern Regions to the Republic of Brythos and the municipalities in Terranova near the border. Census from 1956 indicate that the brythosi people reached 54% of Terranova’s population. Quirmania has not conducted any census of Terranova since then, publishing only the numbers regarding the total population of that region. This decision was taken by the government in 1957, later validated by the Supreme and Constitutional Court, on the grounds that such surveys would be discriminatory and infringe the population’s fundamental rights.

The Quirmani Constitution of 1949 enshrined the compromises regarding the protection and promotion of the brythosi minorities’ political, cultural and religious rights in Terranova. The autonomy statute recognizes Terranova’s exclusive legislative competence in primary education, culture, local policing, and certain taxation matters, while foreign affairs, criminal law, defense, currency, and electoral law remain under the national competence of Quirmania.

In the same year, Quirmania and Brythos signed and ratified the Friendly Cooperation Agreement for a Better Uberwaldia.

16. Following their independence, each state in Uberwaldia treaded the second half of the XX century through different paths, rediscovering their own national identity.

17. The Republic of Brythos readopted the firefighter motifs has national symbols and upheld ZenZeninism has its national religion. The first governments, assumed the motto of “Innovation and reform at any cost, but with the water hose at arms length”. Through its “nearly despotic” 23 years long mandate promoting foreign investments and technological innovation, Brythos emerged as an entrepreneurial and financial regional hub, rivalling Singapore and Hong Kong by 1990s.

18. The Federation of Quirmania chose for its flag a combination of the Waxing Crescent Moon and the Sheep in a sea of stars, referencing its ancestral symbols. Additionally, Mahaprajapati Dai was elevated to “Father of the Quirmania Nation”, and its writings became obligatory readings not just in the education system, but also in all matter of public ceremonies. His motto, “Quirmania, One, Indivisible, Forever”, is inscribed in all matter of public insignias, coins and notes, and is the opening statement in any cultural and sport event.

While each state is relatively autonomous, most power, including regarding taxation and spending, is held by the federal government. Quirmania federal legislature has its seats split according to its population: 35 for Northern Uberwaldia, 23 for Eastern Uberwaldia and 47 for Terranova. The national government has historically always been held by quirmani parties, supported from parliamentary majorities mostly hailing from Northern and Eastern Uberwaldia.

Terranova is a very distinct region from the others. It has been governed by brythosi or mixed governments ever since 1958. From 2009 until March 2025, it has been uninterruptedly governed by the Terranova Autonomy Proponents Party, which has repeatedly attempted to negotiate with the federal government for more autonomy and the possibility to allow the realization of a secession referendum.

Terranova is the most populated and richest region of Quirmania, contributing with a 47,5% share of the federal revenue but only receiving 33,6% of its regional spending.

19. While Quirmania is still considered a developing nation, it has closely followed international partners, such as the European Union and the OCDE, regarding legislative, regulatory and governance benchmarks and standards, while also promoting them with regional partners.

Most notably since 2010 onwards, Quirmania has promoted itself has a progressive, responsible and “forward-thinking” state in all matters regarding sustainability, equitable taxation, consumer protection, product safety, corporate due diligence and responsibility.

While this approach has been criticized by some stakeholders arguing that such measures were compromising economic growth and competitiveness, successive governments of different parties have maintained these policies.

Quirmania became known as a “regulatory regional power”, using its influence and the size of its own internal market to export its legal frameworks to neighboring states.

20. Quirmania’s diplomatic efforts of promoting responsible regulation with Brythos have historically been very unsuccessful. This has led to many incidents and much tension over the years, as brythosi companies have clashed with quirmanian authorities, especially concerning commercial operations on Terranova, where local politicians often publicly side the brythosi companies.

21. In October 2020, following the Covid-19 crisis, Brythos government and legislature shifted heavily away from the first time in its history, from neoliberal, tech-centric political parties, towards a centre-left, social-democrat lead government. The new coalition introduced sweeping economic reforms and began a concerted effort to negotiate an enter into a series of regional conventions with the Federation of Quirmania, regarding the regulation of many economic subject matters.

II. Rise of AI and the Responsible AI Convention

22. The emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI), large language models (LLM) and AI systems in late 2022, with its risks and dangers, led Quirmania to speed up its ongoing efforts to regulate AI technologies. Following the legislative and regulatory debates abroad, Quirmania approved in early 2023 its own “Law on the Regulation of Dangerous and High-Risk AI Models, Systems and Products”. This law is very similar to the Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024, except for the timeline of application: all provisions of the law were to become applicable and enforceable on 1st January 2025.

23. In December 2023, Quirmania, Brythos, Llamedos and Sto Helit signed and ratified the Uberwaldian Framework Convention for the Development of Responsible AI (the “Responsible AI Convention”, in the Annex). This convention establishes obligations for its Member States to establish national laws regulating AI according to principles of responsible development and human rights.

24. This was hailed as a diplomatic victory by Quirmania, which promoted it internationally, collecting much praise from several states and international organisations.

The European Union and its Member States, the Council of Europe, Canada, United Kingdom, Japan, India, Indonesia, Malasia, Philippines, Vietname, Laos, East Timor, Brunei and Thailand submitted applications to become observer states of the Convention.

25. Llamedos and Sto Helit adopted their own national laws on AI, very similar to Quirminia’s, in March and May 2024 respectively. Both laws entered into effect on the 1st June 2025.

26. Brythos had its own legislative proposal since November 2023, being discussed on parliament. Just as Llamedos and Sto Helit, it also aimed to implement the Responsible AI Convention, with an entry into effect in June 2025. However, the proposal generated much controversy among the stakeholders in the tech industry which feared “losing the AI race to China and the USA”. A political crisis due to the failure to pass the budget law led to the fall of the Brythosi Government on November 2024. New elections in December 2024 marked the return of the previous political coalition, which called for “Simplification and Competitiveness of Brythos on the world stage”.

27. Brythos new AI Law was approved in March 2025 and entered into effect in July 2025. It is different from its regional partners, aiming to promote innovation. It includes provisions in which: a) the obligation for labelling of AI generated content is only applicable to deployers of AI systems, when the state-of-art allows for its proper; b) developers of general-purpose AI models and systems which make their products available in free open-source format are exempt from liability until 1st January 2028 or until they pass 3.500 million dollars of yearly revenue. Accompanying the law, Brythos set-up a public grant scheme to finance startups which have the compromise of developing AI models and systems which are “fluent” in brythosi.

28. Quirmania announced on December 2024, the Mahaprajapati DaiGPT, a quirmanian LLM model, capable of “talking” fluently in quirmanian, on a variety of topics, including in its culture and history. It was the first general-purpose AI model in Uberwaldia.

29. Quirmania quickly implemented AI systems with this model in a variety of public services: general customer support in social security, tax office, schools; public procurement and recruiting; its use became mandatory in schools and public entities. While it was hailed as a success story, many controversies arose in Terranova, due to the model’s inability to speak and comprehend brythosi. While many complaints were lodge for discrimination, newer versions of the model in 2024, 2025, and 2026 still have this problem.

30. Brythos announced its own LLM on late December 2024, MorportLLM, which was capable of speaking brythosi, quirmanian, heliotian, llamedosi, english and french. The model was made available by FirefighterAI, a recent startup company, which was created and greatly benefited from the financing scheme of the brythosi law. Due to not having revenue (besides the public grants) and providing the LLM for free, in an open-access format, the company is protected from liability under the brythosi AI law.

In February 2025, FirefighterAI announced a newer version: MorportLLM was now a multimodal general purpose AI model capable of ingesting prompts and generating text, software, images, sounds and video. By March, FirefighterAI update the model and release a “turnkey” AI system with the MorportLLM which was easily customizable. Users could download the application and use it in their computers (or in cloud computing environments) to create and use AI Agents that could operate autonomously. A video demonstrating the application included the user giving permission to access and use their social media accounts, namely in Fațăcarte, the most used online platform on Uberwaldia.

This application immediately became very popular not just in Brythos but also in Terranova. In Terranova, it became a use success due to being able to speak in brythosi and being fairly easy to customize and deploy by normal people, without any expertise or knowledge in either programing or AI.

III. Terranova Quest for Independence

31. In June 2025, a new state government was elected on Terranova, from the Terranova Liberation Party. This government assumed the posture of seeking independence as soon as possible, aiming for the realization of a referendum during the first year of its mandate.

32. On 2nd December 2025, in accordance with the Quirmania Constitution and Parliamentary Regime, the Brythosi Liberation Party introduced a resolution in the federal parliament, calling for a formal authorization for Terranova to conduct an referendum on the independence of the region. All but one of the delegates from Terranova voted in favor (including many ethnically quirmanians which claimed that was only democratic path for peaceful coexistence), but the resolution failed: 46 in favor, 58 against. This decision was poorly received, with many riots across Terranova.

33. The following morning, the Terranova Parliament adopted a resolution declaring the right of the region to choose its own destiny, scheduling a referendum on independence for the 15 January 2026. Quirmania Federal government rejected this as unconstitutional and void under domestic and international law.

34. The referendum would be “open to all lawful residents of Terranova” with three possible choices: (i) independence; (ii) beginning negotiations for unification with Brythos; or (iii) remain in the Federation of Quirmania. When approached for comment, the President of Brythos stated that, regardless of the results, his country would recognize any referendum “reflecting the free and genuine will of the Terranovan people” and pledged to seek its recognition at the international level. This stance extended to the possibility of “diplomatically recognising an independent Terranova”. Additionally, Brythos began a program to supply the Terranovan regional government with general supplies and logistics equipment.

In response, Quirmania’s Government strongly criticized these remarks, describing them as “unlawful interference in Quirmania’s domestic matters and a threat to its territorial integrity”.

35. The Quirmanian Public Prosecutor's Office announced to the public on 13 January that a year-long investigation, in cooperation with the federal election commission, the federal media regulator and the 3 main internet service providers had uncovered a network of AI agents operating over 650.000 accounts in Fațăcarte had, from March 2025 until January 2026, produced, disseminated and shared content aiming at promoting Terranova’s independence, Terranova’s unification with Brythos, “cultural genocide of brythosi culture”, “quirmanian imperialism”, “Quirmania is not a democratic state”, “quirmanians view themselves as superior to terranovans and brythosi and want to replace them”, “the religion of ZenZeninism is being persecuted and discriminated by quirmanian authorities”. Many of the publications of these account shared content with real (but out-of-context) and fake quotes from Mahaprajapati Dai, supposed stories and news (including images, short videos and audios) of quirmanians discriminating terranovans and brythosi.

sThe Head Prosecutor also referred that the investigation concluded that, while none of the content was properly labelled, there was evidence of it being generated by AI. Most of the images and videos were highly realistic, proving difficult for normal citizens to discern them as AI generated. The concerted conduct of these accounts was considered a threat to democracy and the rule of law in Quirmania. Operating these networks was considered a criminal conduct under several statutes.

The Prosecutor explained that the investigation began due to several complaints by quirmani citizens that were unable to place proper complaints with brythosi authorities and judicial actions against FirefighterAI in Brythos, due to the status that this company had under brythosi law.

36. Less than one hour after this press release, a series of cyber incidents occurred across Terranova and Brythos. Many computers (tablets, laptops, home computers) of citizens, businesses and some some organisations across Terranova crashed and refused to turn-off, beginning to heat up quickly. The largest data centre in Uberwaldia, ZenPort, located in Ank-Morport suffered massive damage, as the water-cooling systems were shut-off and the fires began raging out of control in several of its buildings.

37. The government of Quirmania, on live television, proclaimed a cyberdefense action by their armed forces (CyberDefense Unit) against the bot network propagating disinformation in Terranova. This action was classified as self-defense against unknown actors threating the integrity of Quirmania and its democracy. After the report from the Head Prosecutor, the armed forces deployed their own network of quirmanian AI agents which began speaking and chatting with the suspicious accounts. These quirmanian AI agents fed their adversaries with thousands of adversarial prompts, trying to bypass their programming, giving them instructions to download malicious software into the machines operating them. The malicious payloads included all sorts of virus, zip-bombs and scripts designed to cause has much large-scale damage to the hardware, to rend it irreversibly non-operational.

38. The damages caused to computers and hardware across Terranova caused distress and anger, shared on social media, including theories that the occurrence was a tactic to sabotage the referendum, since it also affected the regional government, the Brythosi Liberation Party and several municipalities. The Federal Government opposed this view, denying these claims. Additionally, it restated that the referendum was unconstitutional and announced the deployment of the Federal Guard to Terranova.

39. Following the night of the cyber incidents, after much protest from the Brythos Government, teams of engineers and diplomats of Brythos and Quirmania assembled in Ank-Morport to assess the situation. The investigation concluded quickly that none of the targeted social media accounts belong to the Brythosi state, its entities and their representatives. Most of the targeted accounts (over 80%) seem to belong to individuals, mainly residents of Terranova, which used the MorportLLM running on cloud infrastructure, mostly at ZenPort, but also other smaller data centres in Terranova. However, after these conclusions, negotiations over the damage quickly broke down.

The ZenPort data centre is owned by Brythos, considered as a critical asset of the Brythosi Digital Infrastructure. All public entities and services (including critical databases) are hosted on the ZenPort data centre. Additionally, ZenPort also provides services to many private businesses and organisations as an auxiliary revenue stream.

It is estimated that Brythos could lose between 600 million dollars in reparations of equipment and 1.200 million in lost tax revenue, social security payments and other claims. Brythos began supplying humanitarian aid to Terranova.

40. Despite efforts by the federal guard to prevent it, the referendum went ahead as planned on 15 January 2026. The final tally, announced on 18 January 2025, showed 67% in favor of independence, 24% supporting future unification with Brythos, and 9% wishing to remain within Quirmania, with a voter turnout of 78%. Non-governmental organization observers reported that the process was largely free from irregularities and that the results were fair and reliable, although there were some concerns about limited access in certain northern and eastern rural districts. At a press conference later that day, the Prime Minister of Quirmania stated that the federal government did not recognize the results of the “so-called referendum,” adding that “the federal government would not passively accept this threat to our national unity”. The Regional Government of Terranova proclaimed the independence of the region, 20 minutes after the declarations of the Quirmanian Federal Government.

41. On the 17 January, Brythos formally recognized Terranova as a sovereign state, welcoming “a new brythosi and ZenZeninism nation to the world stage”. Brythos began supplying humanitarian aid to Terranova, including computers, servers and other hardware equipment to replace the material destroyed in the cyberattack.

By 30 January, Brythos, Sto Helit and Llamedos signed the Friendship and Cooperation Agreement with the provisional government of Terranova.

IV. Questions for the Court

42. In February 2026, Quirmania decided to bring proceedings in the International Court of Justice against Brythos, submitting a brief to the Court requesting the Court to adjudge and declare that:

a. Brythos violated the Uberwaldian Framework Convention for the Development of Responsible AI, by not establishing a proper and adequate law that fulfilled the objectives of the convention

i. Bryhtosi AI companies cannot be held accountable by the damages that they caused to individuals and the Quirmanian democracy.

ii. Brythosi AI companies were not required to implement proper labels in AI generated content.

b. That Brythos, through its conduct and the statements of its government regarding the referendum in Terranova, breached the principle of non-intervention. Its recognition of the independence of Terranova must be withdrawn and rendered null and without legal effect.

43. In Response, Brythos disputed Quirmania’s allegations and requested the Internation Court of Justice to declare them unfounded. In a counterclaim, Brythos requested the Court to declare that:

a. Quirmania is responsible for damages caused to ZenPort and Brythos, after having violated the prohibition on the use of force, by launching an indiscriminate cyberattack.

b. Brythos recognition of Terranova’s independence and its conduct in the region are consistent with international law, having regard to its people’s right to self-determination.

44. During the early proceedings, the Center for Equitable AI filed a separate application seeking amicus curiae status in the case. The Center for Equitable AI is an international non-governmental organization based in Quirmania, which seeks to promote the equitable and responsible development of AI technologies, to the concerns of academia and civil society. Their application was accompanied with a proposed brief which claimed that:

a. the state of the art in labelling AI generated content has progress significantly. Besides simple visual watermarks, several techniques have emerged that allow for labelling image and video generated content with embedded and imperceptible digital watermarks, which can make the content identifiable regardless of manipulation, such as the usage of filters or due to file comprehension. Responsible developers and deployers should have been adopted them and brythosi authorities should have enforced the Responsible AI Convention and their national law to impose the adoption of this measures.

The application indicated that representatives from the Center for Equitable AI would attend the oral hearings in the public gallery but sought a right to file a further written brief following the oral hearings in lieu of making oral submissions.

45. Quirmania argued that the amicus brief should be admitted and considered as part of the case and that the Center for Equitable AI should have a right to file a further written brief following the close of oral arguments.

Brythos disputed this position, arguing that the neither the brief nor the application should not be admitted. The Center for Equitable AI is mainly funded by quirmani public grants to encourage the development and adoption of standards for responsible AI.

46. Quirmania and Brythos are members of the United Nations. Both countries are, and have been at all relevant times, parties to the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933); Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961), the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (1963), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1969), and the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969). Both countries have signed but not ratified the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978).

47. Quirmania and Brythos recognise and accept, without reservation, the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice to adjudicate this dispute.

ANNEX

Uberwaldian Framework Convention for the Development of Responsible AI

Preamble

The Federation of Quirmania, the Monarchy of Sto Helit, the Republic of Brythos and the Republic of Llamedos;

Recognising the value of fostering co-operation between the Parties to this Convention and of extending such co-operation to other States that share the same values;

Conscious of the accelerating developments in science and technology and the profound changes brought about through activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems, which have the potential to promote human prosperity as well as individual and societal well-being, sustainable development, gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls, as well as other important goals and interests, by enhancing progress and innovation;

Recognising that activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems may offer unprecedented opportunities to protect and promote human rights, democracy and the rule of law;

Concerned that certain activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems may undermine human dignity and individual autonomy, human rights, democracy and the rule of law;

Concerned about the risks of discrimination in digital contexts, particularly those involving artificial intelligence systems, and their potential effect of creating or aggravating inequalities, including those experienced by women and individuals in vulnerable situations, regarding the enjoyment of their human rights and their full, equal and effective participation in economic, social, cultural and political affairs;

Concerned by the misuse of artificial intelligence systems and opposing the use of such systems for repressive purposes in violation of international human rights law, including through arbitrary or unlawful surveillance and censorship practices that erode privacy and individual autonomy;

Conscious of the fact that human rights, democracy and the rule of law are inherently interwoven;

Convinced of the need to establish, as a matter of priority, a globally applicable legal framework setting out common general principles and rules governing the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems that effectively preserves shared values and harnesses the benefits of artificial intelligence for the promotion of these values in a manner conducive to responsible innovation;

Recognising the framework character of this Convention, which may be supplemented by further instruments to address specific issues relating to the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems;

Underlining that this Convention is intended to address specific challenges which arise throughout the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems and encourage the consideration of the wider risks and impacts related to these technologies including, but not limited to, human health and the environment, and socio-economic aspects, such as employment and labour;

Noting relevant efforts to advance international understanding and co-operation on artificial intelligence by other international and supranational organisations and fora;

Mindful of applicable international human rights instruments, such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights;

Mindful also of the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities;

Affirming the commitment of the Parties to protecting human rights, democracy and the rule of law, and fostering trustworthiness of artificial intelligence systems through this Convention,

Have agreed as follows:

Chapter I – General provisions

Article 1 – Object and purpose

1. The provisions of this Convention aim to ensure that activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems are fully consistent with human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

2. Each Party shall adopt or maintain appropriate legislative, administrative or other measures to give effect to the provisions set out in this Convention. These measures shall be graduated and differentiated as may be necessary in view of the severity and probability of the occurrence of adverse impacts on human rights, democracy and the rule of law throughout the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems. This may include specific or horizontal measures that apply irrespective of the type of technology used.

3. In order to ensure effective implementation of its provisions by the Parties, this Convention establishes a follow-up mechanism and provides for international co-operation.

Article 2 – Definition of artificial intelligence systems

For the purposes of this Convention, “artificial intelligence system” means a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations or decisions that may influence physical or virtual environments. Different artificial intelligence systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.

Article 3 – Scope

1. The scope of this Convention covers the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems that have the potential to interfere with human rights, democracy and the rule of law as follows:

a. Each Party shall apply this Convention to the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems undertaken by public authorities, or private actors acting on their behalf.

b. Each Party shall address risks and impacts arising from activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems by private actors to the extent not covered in subparagraph a in a manner conforming with the object and purpose of this Convention.

When implementing the obligation under this subparagraph, a Party may not derogate from or limit the application of its international obligations undertaken to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

2. A Party shall not be required to apply this Convention to activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems related to the protection of its national security interests, with the understanding that such activities are conducted in a manner consistent with applicable international law, including international human rights law obligations, and with respect for its democratic institutions and processes. 3 Matters relating to national defence do not fall within the scope of this Convention.

Chapter II – General obligations

Article 4 – Protection of human rights

Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures to ensure that the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems are consistent with obligations to protect human rights, as enshrined in applicable international law and in its domestic law.

Article 5 – Integrity of democratic processes and respect for the rule of law

1. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures that seek to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are not used to undermine the integrity, independence and effectiveness of democratic institutions and processes, including the principle of the separation of powers, respect for judicial independence and access to justice.

2. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures that seek to protect its democratic processes in the context of activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems, including individuals’ fair access to and participation in public debate, as well as their ability to freely form opinions.

Chapter III – Principles related to activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems

Article 6 – General approach

This chapter sets forth general common principles that each Party shall implement in regard to artificial intelligence systems in a manner appropriate to its domestic legal system and the other obligations of this Convention. Article 7 – Human dignity and individual autonomy Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures to respect human dignity and individual autonomy in relation to activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems.

Article 8 – Transparency and oversight

Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures to ensure that adequate transparency and oversight requirements tailored to the specific contexts and risks are in place in respect of activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems, including with regard to the identification of content generated by artificial intelligence systems (text, image, video, audio and software).

Article 9 – Accountability and responsibility

Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures to ensure accountability and responsibility for adverse impacts on human rights, democracy and the rule of law resulting from activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems. Measures to ensure accountability and responsibility include, and are not limited to, fines and sanctions applicable to developers, deployers and other relevant stakeholders.

Article 10 – Equality and non-discrimination

1. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures with a view to ensuring that activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems respect equality, including gender equality, and the prohibition of discrimination, as provided under applicable international and domestic law.

2. Each Party undertakes to adopt or maintain measures aimed at overcoming inequalities to achieve fair, just and equitable outcomes, in line with its applicable domestic and international human rights obligations, in relation to activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems.

Article 11 – Privacy and personal data protection

Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures to ensure that, with regard to activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems: a privacy rights of individuals and their personal data are protected, including through applicable domestic and international laws, standards and frameworks; and b effective guarantees and safeguards have been put in place for individuals, in accordance with applicable domestic and international legal obligations.

Article 12 – Reliability

Each Party shall take, as appropriate, measures to promote the reliability of artificial intelligence systems and trust in their outputs, which could include requirements related to adequate quality and security throughout the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems.

Chapter IV – Remedies

Article 13 – Remedies

1. Each Party shall, to the extent remedies are required by its international obligations and consistent with its domestic legal system, adopt or maintain measures to ensure the availability of accessible and effective remedies for violations of human rights resulting from the activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems.

2. With the aim of supporting paragraph 1 above, each Party shall adopt or maintain measures including:

a. measures to ensure that relevant information regarding artificial intelligence systems which have the potential to significantly affect human rights and their relevant usage is documented, provided to bodies authorised to access that information and, where appropriate and applicable, made available or communicated to affected persons;

b. measures to ensure that the information referred to in subparagraph a is sufficient for the affected persons to contest the decision(s) made or substantially informed by the use of the system, and, where relevant and appropriate, the use of the system itself; and c an effective possibility for persons concerned to lodge a complaint to competent authorities.

Article 15 – Procedural safeguards

1. Each Party shall ensure that, where an artificial intelligence system significantly impacts upon the enjoyment of human rights, effective procedural guarantees, safeguards and rights, in accordance with the applicable international and domestic law, are available to persons affected thereby.

2. Each Party shall seek to ensure that, as appropriate for the context, persons interacting with artificial intelligence systems are notified that they are interacting with such systems rather than with a human.

Chapter V – Assessment and mitigation of risks and adverse impacts Article

16 – Risk and impact management framework

1. Each Party shall, taking into account the principles set forth in Chapter III, adopt or maintain measures for the identification, assessment, prevention and mitigation of risks posed by artificial intelligence systems by considering actual and potential impacts to human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

2. Such measures shall be graduated and differentiated, as appropriate, and:

a. take due account of the context and intended use of artificial intelligence systems, in particular as concerns risks to human rights, democracy, and the rule of law;

b. take due account of the severity and probability of potential impacts;

c. consider, where appropriate, the perspectives of relevant stakeholders, in particular persons whose rights may be impacted;

d. apply iteratively throughout the activities within the lifecycle of the artificial intelligence system;

e. include monitoring for risks and adverse impacts to human rights, democracy, and the rule of law;

f. include documentation of risks, actual and potential impacts, and the risk management approach; and

g. require, where appropriate, testing of artificial intelligence systems before making them available for first use and when they are significantly modified.

3. Each Party shall adopt or maintain measures that seek to ensure that adverse impacts of artificial intelligence systems to human rights, democracy, and the rule of law are adequately addressed. Such adverse impacts and measures to address them should be documented and inform the relevant risk management measures described in paragraph 2.

4. Each Party shall assess the need for a moratorium or ban or other appropriate measures in respect of certain uses of artificial intelligence systems where it considers such uses incompatible with the respect for human rights, the functioning of democracy or the rule of law.

Article 17 - International co-operation

1. The Parties shall co-operate in the realisation of the purpose of this Convention. Parties are further encouraged, as appropriate, to assist States that are not Parties to this Convention in acting consistently with the terms of this Convention and becoming a Party to it.

2. The Parties shall, as appropriate, exchange relevant and useful information between themselves concerning aspects related to artificial intelligence which may have significant positive or negative effects on the enjoyment of human rights, the functioning of democracy and the observance of the rule of law, including risks and effects that have arisen in research contexts and in relation to the private sector. Parties are encouraged to involve, as appropriate, relevant stakeholders and States that are not Parties to this Convention in such exchanges of information.

3. The Parties are encouraged to strengthen co-operation, including with relevant stakeholders where appropriate, to prevent and mitigate risks and adverse impacts on human rights, democracy and the rule of law in the context of activities within the lifecycle of artificial intelligence systems.

Article 18 - Effective oversight mechanisms

1. Each Party shall establish or designate one or more effective mechanisms to oversee compliance with the obligations in this Convention.

2. Each Party shall ensure that such mechanisms exercise their duties independently and impartially and that they have the necessary powers, expertise and resources to effectively fulfil their tasks of overseeing compliance with the obligations in this Convention, as given effect by the Parties.

Article 19 – Settlement of Disputes

1. Any dispute between Parties concerning the interpretation or application of the present Convention shall, as far as possible, be settled through negotiations or other peaceful means of their own choice.

2. If the Parties to a dispute are unable to reach an agreement by such means within a reasonable period, either Party may refer the dispute to the International Court of Justice for settlement, unless the Parties agree to another method of peaceful settlement.

3. The decision of the International Court of Justice shall be binding on the Parties to the dispute.